I’m working in Disability Studies in my current grad program, and one of the loudest themes to emerge from 21st century disabled communities is the importance of VISIBILITY. Disability visibility–narratives of the lived experiences of disabled people–is crucial in combatting the stigma, misconceptions, and marginalization of people with disabilities, mental illness, and chronic illness, for a lot of reasons that I won’t go into here, because I’m writing about particular misconceptions about a specific mental illness.

I want to right these misconceptions not because I love being right (which I do), but because misconceptions lead to misdiagnosis, lack of diagnosis, and in some cases, worsening of symptoms, incarceration, institutionalization, and suicide. Visibility is not just beneficial, it’s essential for the surviving and thriving of disabled people. As I read and learn, the more I have begun to realize that I myself am not living visibly as a person with a disabling mental illness. I haven’t told most people in my life, because of my own internalized ableism–I’m afraid of the resulting stigma, that I won’t be believed, that I’ll be treated differently, a whole bunch of stuff.

Anyway, I have Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. I will write about my personal experiences with it elsewhere, as it’s a long and interesting story that’s not super relevant here. I was diagnosed in my thirties, but I have had it since childhood. Everyone that knows me well knows that I’ve struggled with debilitating anxiety since I was a child. I have had a lot of really difficult years. When my first psychiatrist diagnosed me, she was surprised I’d made it till my thirties without institutionalization or worse. I was strong, I was lucky, but mostly, I was privileged enough to stay well that long without any professional support. She also warned me that I needed treatment, and I didn’t take that seriously until my forties.

These days, I see my whole life through the lens of OCD: I have individual and group therapy, I do daily Exposure and Response Prevention, I write and read about anxiety and mental illness, and I belong to many online OCD groups. I also take medication and have an extensive network of emotional support. Now that I have these supports, my life makes so much more sense, my brain makes more sense, and that is a tremendous blessing, especially for someone like me who is always trying to make sense of things.

While OCD is legally and medically a psychiatric disability, for which I am able to claim a variety of accommodations, I am uncomfortable referring to myself as disabled, and part of this is internalized ableism again, but it’s also because of my own immense privilege: I am white, pretty, mobile, verbal, and I have been financially stable for the last ten years or so. I have insurance, a car, a loving supportive partner, and colleagues who support me in all the ways I show up: as a smart academic, an enthusiastic teacher, a devoted writer, and as a person with mental illness. I am also really good at masking, which means, for me, acting like everyone around me so that I’ll be, for the most part, accepted. Most people with OCD, and other mental illnesses and disabilities, do not have these privileges and it’s difficult for me to claim and acknowledge my disability when it’s so much less impactful on my life than theirs.

But that’s just why it’s important to me to be visible now. My privileges make it safer for me to disclose my lived experience, and any increase in visibility benefits the disabled community in general. Part of my ease in sharing this with everyone now is due to the folks around me who are so proudly, visibly disabled humans who do not apologize, diminish, hide, or excuse their experiences.

Right now, my anxieties tell me that many of you are saying, “OCD? That’s not a disability! Aren’t you just really organized and like things symmetrical?” Or maybe you’re thinking, “her OCD can’t be that bad. She’s not a hoarder, she doesn’t pick her hair or skin (trichotillomania), she doesn’t have to count all her steps or do any of those things Jack Nicholson did in As Good As It Gets.” The reason I think you may be thinking those things is because…people have said these things to me, over and over when I’ve disclosed my OCD. The most common response is “ha ha me too,” thinking I mean that I like things to be “a certain way.” (If you don’t believe me, go to Google image search and type in “OCD.” What comes up? Type it into Facebook and see what you find. Bring it up in conversation with literally anyone and ask them what they think OCD is.)

So here I want to clarify what OCD is, from my own experience and research, and hopefully to correct some misconceptions that many of you must have. OCD is preposterously misunderstood in popular media and socially. Unless you do a lot of research or have a loved one who has OCD and is vocal about it, most of the world has no idea what it is…actually, no, that’s not right: most of the world has an incorrect idea of what it is. All mental illnesses are portrayed poorly in popular media, but OCD has the unlucky distinction of being the one most frequently portrayed as being a joke, a quirk, a personality trait, rather than as what it is: a disabling psychiatric illness.

Like every mental illness, OCD manifests differently in every person who has it. I’ve met many other folks whose lives and symptoms were drastically different from mine, but there are some similarities. The primary thing that we share (unhappily) is intrusive thoughts. All humans have unwelcome thoughts that pop into our brains throughout the day, but for us, we can’t let go of them. We latch onto them, fixate on them, and many of us are intensely worried that we will act on them. They can be something like “what if I ran over somebody with my car on that last block but didn’t notice,” “what if I accidentally used a racist word when talking to my friend,” or, for me, it can be “what if my cat has cancer and this is his last day on earth” or “what if this delicious food I’m enjoying is riddled with salmonella and I’m going to spend the rest of this week on the bathroom floor?”

Although everyone has intrusive thoughts, when folks with OCD have them, we experience a very strong anxiety. This is not garden-variety anxiety, this is suffocating, terrifying fear–our bodies and minds go into fight-or-flight mode. Just typing that sentence about salmonella, my heart began to race, my breathing increased, and I started feeling physically ill. My jaw clenched, and my whole brain cramped up trying to expel that intrusive thought. Fight or flight means that your body is responding to the fear (of the intrusive thought) the way it would to, say, seeing a bear in the woods or finding a black widow spider on your leg. People with OCD experience those thoughts not as thoughts or fears, but as something real. It’s hard to explain, but I can say that when I have these thoughts, my body responds to them as if they were reality. Like, if you try to tell me I’m wrong, I won’t believe you.

I’ve had days…honestly, weeks, where I was in a continued heightened state of fear due to a thought I had and the resulting terror that it might come true. For me, it’s usually that something bad will happen to a loved one, but intrusive thoughts vary by the individual. They are usually the thing most antithetical to our values, the thing most horrific to imagine. For a loving parent, they may fear killing or hurting their child; a religious individual might fear committing a sin; a devoted spouse might fear cheating on their partner. Like I said, there is something about OCD that convinces you that that horrific thing has happened, is happening, or will happen. We’re not delusional–everyone with OCD knows that their fears are irrational. But our bodies don’t, because of a process I’ll try to describe below.

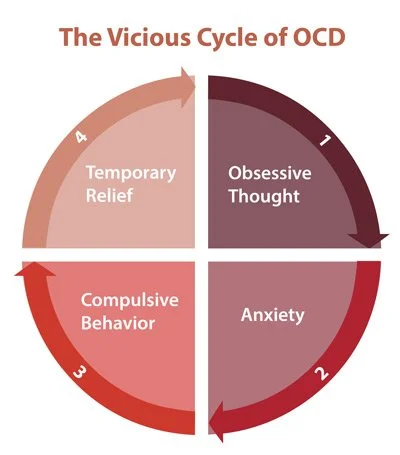

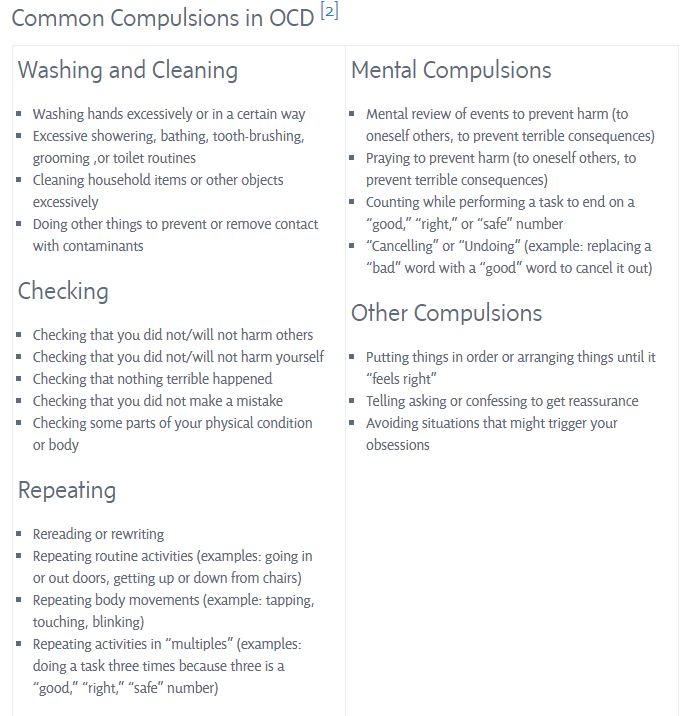

That first part–the intrusive thought and the resulting fear and fixation–is the Obsession. Next, the Compulsions kick in. This is the part of OCD that’s better-known. A person with OCD has an intrusive thought and is afraid and disturbed by it–then they get this weird idea that if they do something they can prevent the bad thing from happening. You know how someone says “I never get sick!” and you get a pit in your stomach until you reach out and quickly knock on wood? And then, after you knock, you feel kind of relieved, like you took care of the problem? That’s exactly what it’s like. At some point in our development, we tried to find a way to cope with our extreme terror, and we found compulsions–we perform some random, ritualized act, believing that it will neutralize the fearful event. The relief we get from performing these compulsions gives us a sense of control over the situation and over the thing we fear. You’ve seen folks do compulsions in the movies on TV–touching things a certain number of times, repeatedly clearing their throat, avoiding cracks in the sidewalk, scrubbing their houses clean.

So the problem (well, one of the problems) with this process is that when we perform the compulsion, we get a bit of relief, a positive feeling of pleasure and control. After the exhausting and debilitating fear, this relief is addicting, so we want to do it more. This cycle continues, and then, eventually, when we experience a random fear or intrusive thought (which, again, is very normal for everyone), our first reaction becomes the desire to perform the compulsion. This then makes the fears even less tolerable, the compulsions more of a relief, and we get stuck in this cycle that it’s hard to extricate yourself from. And OCD doesn’t even stop there–it starts to tell you that you didn’t do the compulsion quite right–maybe your mind wasn’t perfectly clear when you did it, maybe you were standing on the wrong foot. Better try doing it again. And again. So we’re driven to do more.

It’s important to clarify that the urge to perform a compulsion has a lot of pressure behind it: we’re doing it to prevent the fear from coming true. So when we’re, say, touching a light switch nine times, we might be doing it because we are trying to prevent our father from dying. Our brain tells us that we can prevent this devastating thing from happening by just touching the light switch. So if we don’t touch it, it’s like choosing to kill him. I highlight this in order to explain that it is very, very difficult for us to “just stop,” and also to emphasize the emotional weight and stress around these obsessions/compulsions. This is the part of OCD that is almost never depicted in popular media. Why did Monk have to touch all those lightbulbs? Why did Emma from Glee have to wash all her food? Why did Jack Nicholson’s character have to skip all the sidewalk cracks? Those elements of their stories are missing from these narratives of OCD.

It’s important to me that you hear our side of this. When my OCD was at its worst, I spent literal hours walking in and out of the same doorframe in my apartment, because if I didn’t do it just right, a loved one would die. I spent days like that, consumed with different fears, many times throughout my life: I couldn’t go to work, I couldn’t leave the house, I couldn’t shower. I was utterly exhausted from my body and mind being on high alert for such an extended period of time. I remember friends or family would call, and I would try to articulate what my life was like…how could I possibly describe. Those days were endless. It’s tiring holding the universe together on your own.

Now, imagine going into work after a night like that. Imagine you get brave and trusting and decide to reach out to a coworker you feel safe with and disclose your experience. You tell them you have OCD. They reply, “ha ha me too! I am sooooo organized, you should see my planner!”

Because we only talk about and see in media the compulsions, and we don’t see and experience the terror and anxiety of the obsessions, it makes sense that folks think of OCD as a quirk, as a funny or silly disorder. But it is not–it is a painful, exhausting, destructive, and disabling mental illness.

Another element of OCD that is often overlooked is that many OCD sufferers have compulsions that are completely invisible–this is mostly how OCD manifests in me. For us, our compulsions are internal and mental. We try to force our brain to think one way or another, or to think a thought perfectly. For example: I’m driving, and someone does something jerky. I get angry and think “I hope they get into a car accident.” This is a horrific intrusive thought for me–my brother and his wife died in a car accident and I’d never wish that grief on anyone, anyone, ever. I get so upset by that intrusive thought that my brain begins to race. I begin trying to “un-do” that thought in my mind. I try to, in my mind, re-visit the moment before that thought and think something else instead. Maybe: “I hope that person has a nice day.” Or I might try to clearly visualize that person being safe and happy, or I might repeat a positive phrase like an affirmation. So at any given moment, inside my mind, I’m experiencing terrifying intrusive thoughts and then immediately engaging in some sort of ritualized mental compulsion.

Folks with invisible compulsions like mine often don’t seek out diagnosis or treatment, because what we experience doesn’t “look like” the OCD we see on tv or movies, and so we don’t realize that what’s happening inside our brains is not typical. I suffered with my symptoms for 30 very tiring years because I didn’t meet the stereotype of the clean freak with the quirky compulsions–I’m a lifelong, relentless slob, and I didn’t have any external compulsions (the doorframe thing came later!). In my case, my misconception of what OCD was prevented me from seeking and accessing the help I needed.

And it’s not just regular folks like me who have misconceptions about OCD: many or most medical and mental health professionals are entirely uninformed about it (ask me how I know!) and do not recognize OCD when it manifests. Many more of these professionals have no idea that standard therapeutic methods for anxiety may actually make OCD worse, and often does. OCD is treatable, but the treatment is very specific and different than for other psychiatric illnesses. This means that there are a lots of us out there who are either lacking a diagnosis due to misconceptions about OCD, and those of us who have a diagnosis are not getting appropriate treatment, and may be, in the meantime, absolutely destroying our bodies with anxiety, alienating friends and lovers, losing jobs, self-medicating with addicting substances–I could go on.

But wait, it gets worse: People of color are just as likely to experience OCD as white people, but they are far less likely to receive diagnosis or treatment for the disorder. This is directly due to the combined effects of racism and the lack of visibility of what OCD actually looks like. People of color who share their symptoms with their doctors are more likely to be misdiagnosed with psychosis and/or to be perceived as violent and dangerous. If you don’t understand why, imagine this: two women, one white, one Black, confess to their doctors that they are worried they might kill their baby. Which will be reassured and sent to therapy? Which will have CPS/police sent to her home?

“Research shows that African Americans are consistently over diagnosed with psychotic disorders and more likely to be hospitalized, even after controlling for severity of symptoms and income…Given the bias toward a psychotic diagnosis for this group, it is possible that African Americans with the most severe OCD, especially those with unusual obsessions or compulsions, may be misdiagnosed as psychotic”

International OCD Foundation

Speaking so loudly about my own experience of a disabling mental illness is a bit of a risk, especially for a super shy and private person like me, but I trust you can see now why it’s important for me to do so. I’ve always been frustrated by humanity, and how much of our actual lived experiences we keep secret. I hope that by sharing my own diagnosis (well, really, just one of them–but that’s for another blog post!) I can encourage others to do so, and over time, I hope, we won’t be so in the dark about mental illness and disability. Visibility is crucial:

increased visibility of the actual lived experience of OCD will save lives. It will benefit those who have been suffering for years, trapped inside their own minds by a disorder that few recognize or understand.

The years I went untreated took a lot out of me. I suffered a lot more than I needed to. I’m in a much better place now thanks to treatment, and I feel a hope I haven’t felt for a long time–that maybe I can still enjoy my life, make friends, and create beautiful things as much as I want to. As I grieve the time I lost, I also feel committed to making sure that other folks won’t have to. So here I am, being visibly mentally ill. Deal with it!

For more information on OCD, a good source is the International OCD Foundation.

You described ocd perfectly. I have suffered with this horrible illness since I was very young. (I’m now 51) It has held me back from being able to fully enjoy life. I am finally learning how to cope a little better thanks to therapy and medication. Eventually I will find my joy. 😁 Awesome post.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for saying so! Wishing you all the best. ❤

LikeLike

What a rich read this was! Full of good examples, research, charts & graphs (yay, love visual information) … and STUNNING writing. My favorite part/paragraph was the opening declaration here:

>> “I want to right these misconceptions not because I love being right (which I do), but because misconceptions lead to misdiagnosis, lack of diagnosis, and in some cases, worsening of symptoms, incarceration, institutionalization, and suicide. Visibility is not just beneficial, it’s essential for the surviving and thriving of disabled people. As I read and learn, the more I have begun to realize that I myself am not living visibly as a person with a disabling mental illness. I haven’t told most people in my life, because of my own internalized ableism–I’m afraid of the resulting stigma, that I won’t be believed, that I’ll be treated differently, a whole bunch of stuff.” <<

I've already shared it forward with two of my family members (and favorite people in the world). Thank you, PZR!

LikeLiked by 1 person